Are Journalists to Blame for School Shooting Contagion?

In the week following the school shooting at Apalachee High School on September 4, 2024, police across the United States saw a surge in reports of threats targeting schools.

In one such case, a 14-year-old girl was charged with threatening a shooting at her Yorktown, VA high school after a school resource officer at Tabb High School learned that she had posted a threat on social media to “shoot up the school,” according to a news release.

The unnamed student was charged with one felony count of making threats of bodily injury to persons on school property. The York County Sheriff’s Office determined that the girl did not have the means necessary to carry out her threat, though they did not divulge what that meant. Was her threat the result of social contagion following news coverage of the then recent school shooting in Georgia?

In the “Trends and Conclusions” article from our series “History of School Shootings in the United States,” we examined a wide array of claims related to the causes of school shootings.

Among them were supposed psychological profiles of school shooters and statistics related to media coverage, and we thought both deserved another look, along with a look at some of the recommendations made to media about how to cover these stories.

A study review published by the American Psychological Association highlights one study which found that, on average, widespread media coverage of school shootings brings a temporary increase in the probability of more school shootings that lasts 13 days, with at least 22% new school shooting incidents that are less than 1% likely to be random.

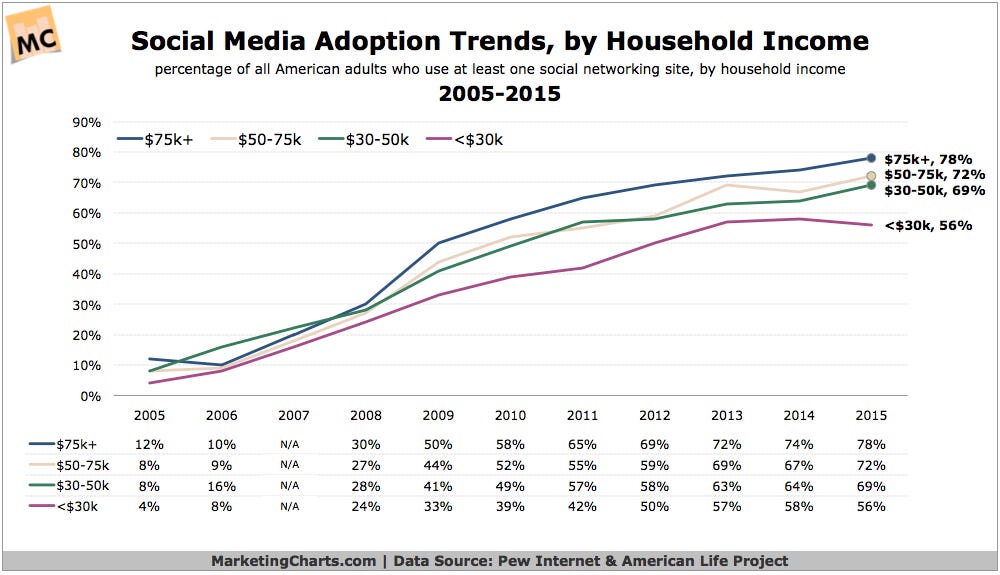

Social media in particular increases this risk, and we noted an interesting though inconclusive point in our trends and conclusions article:

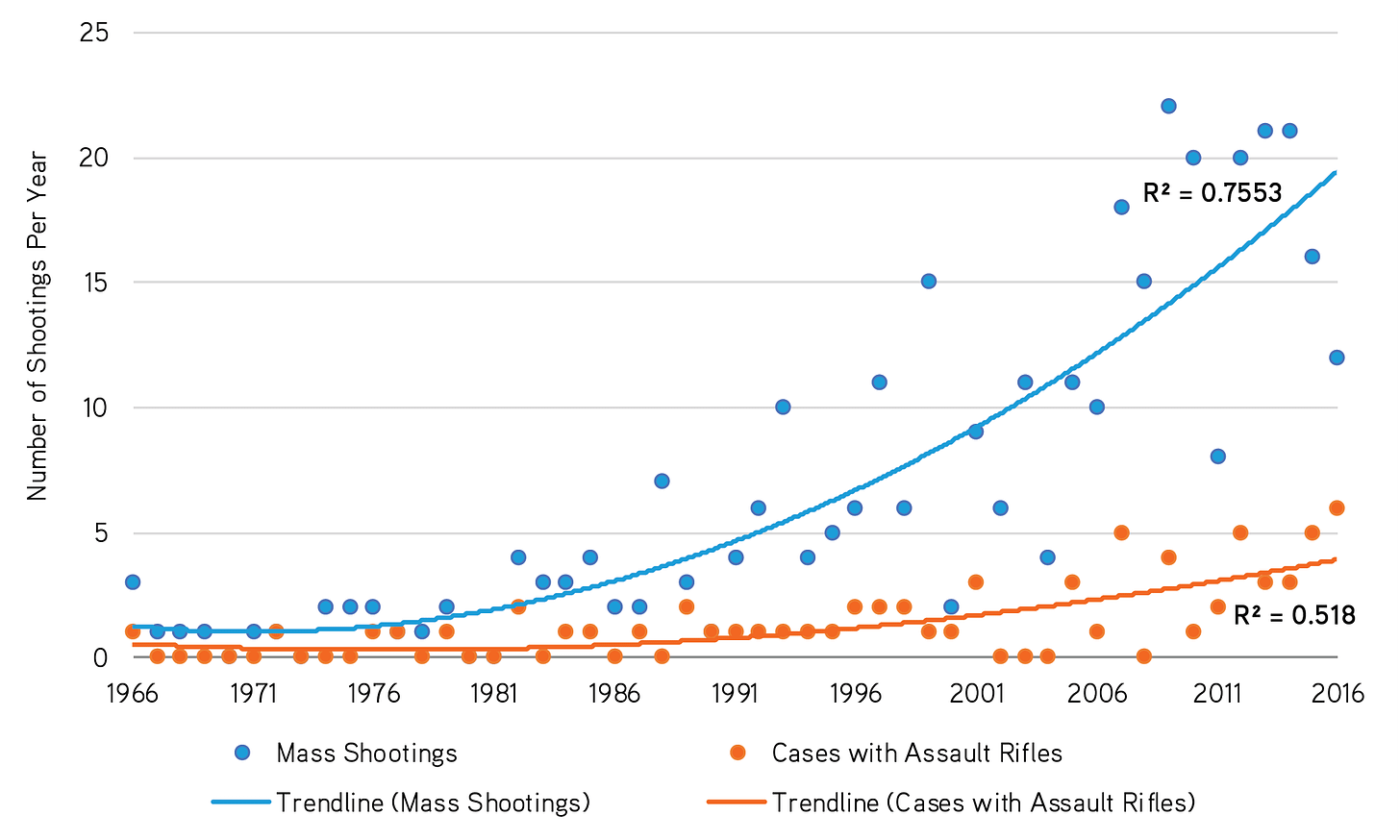

The overall increase in both mass shootings and school shootings roughly mirrors the rise in social media adoption, particularly if you look back to bulletin board systems as the first forms of emergent social media. The first public dial-up BBS went online on February 16, 1978. Note the shooting trend line below.

Garcia-Bernardo et al showed that there is a ratio between time to attention in which tweets about school shootings above a certain threshold (ten per million users) increases the probability of a school shooting in the next eight days up to 50%.

If that same amount of attention is sustained to nineteen days following a shooting, the probability of another shooting increases to 85%, and if it is sustained out to 35 days following a shooting, the probability of another shooting increases to nearly 100%.

The first ten days after an attack were shown to be the most crucial for social contagion for another attack, especially when tweets about the shooting reach more than 45 per million. They also found that the total number of tweets was linked to a higher number of fatalities in subsequent shootings.

The framing of the media attention received by these shootings matters a lot in terms of the impact on subsequent shooting incidents. In an analysis of hundreds of New York Times articles, it was determined that the media focused much more heavily on the shooter than the victims.

Media coverage tends to focus on the suspect, followed by coverage on victims, societal impact, and possible causative motivations. Gun control has become the focus in the vast majority of these stories; by contrast, mental health issues were the focus of less than half despite mass shooters being more than twice as likely to have a psychiatric diagnosis compared to the general population.

Schildkraut and Elsass suggest that extensive news coverage of methods and motivations inspires copycat killers, giving them a blueprint to follow, and that media glorification of school shooters provides copycats with models they can identify with and emulate.

A study review on the Changing Media Frames of School Shootings mentions that news published by USA Today and The New York Times persistently frames school crime as getting worse, distorting the public perspective to suggest that the number of shootings has increased (Schildkraut et al) despite evidence that the number of these events have declined (Haan & Mays).

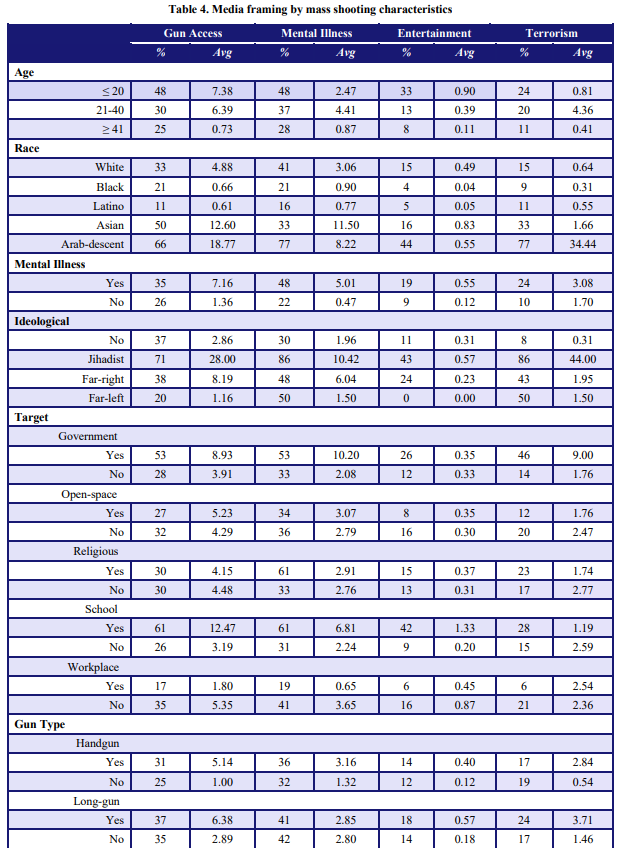

A study published in Criminology, Criminal Justice, Law & Society found that the media consistently employs just four frames, and these vary largely based on the demographics of the perpetrator: Gun Access, Mental Illness, Entertainment, and Terrorism.

The same study also found that,

…gun access framing was more likely when mass shootings involved government targets. This finding is, in part, due to the Tucson shooting; the only government target in the top five incidents that included gun access framing.

This supports previous research suggesting that rhetoric around the Tucson shooter often focused on how he was able to access his weapon, despite his history of mental illness, as well as his parents’ attempts to take his guns away from him (Hollihan & Smith, 2014)

and that while school shootings were often framed under the auspices of gun access,

…school shootings also increased mental illness and violent entertainment frames. This supports previous research finding that school shootings are often framed using these three “usual suspects” (Schildkraut & Muschert, 2013).

The APA study review also mentions an FBI threat assessment report on school shooters which lists depression as a major predisposing factor to mass shootings at schools, that approximately one of every four adolescent shooters had earlier psychiatric treatment (compared to 50% of adult mass shooters), and that one of the three primary diagnoses adolescent shooters received was depression.

Vossekuil et al showed that 78% of schools shooters had thoughts of suicide or had prior attempts at suicide, while Weisbrot determined that higher levels of threat were posed by the most socially lonely or teased and bullied, particularly those who were harboring secret retaliatory thoughts.

The APA study review notes that the isolation may be the consequence of “trademark narcissistic behavior,” and that many mass shooters exhibited a tendency towards externalized blame, with individuals who were identified as being troubled and offered help rejecting any insinuation that they might be the problem.

The narcissistic tendency towards victimization as a rationalization for the mass murder of random victims was also noted by additional researchers, with many finding paranoia, persecution, and resentment to be a common elements in the profiles of mass shooters.

Meloy et al note that identifying with or copying the behavior of admired others is a primary defense of narcissistic individuals; that is, school shooters want to believe they are as aggressive, tough, militaristic, etc, as other killers that they admire because it makes them feel better.

The study review goes on to note that the three primary risk factors for mass shooters of social isolation, depression, and narcissism are intertwined and feed each other. Fame and aggrieved entitlement act as a kind of salve for isolation, depression, and narcissism.

Lankford suggests that the seemingly random nature of these shootings may be by design, which is to say that attackers seem to recognize that acts of mass murder against random, innocent victims are an attempt to compensate for years of feeling like failures, losers, victims, outcasts, etc, in a desperate bid for attention, social recognition, and perceived glory through revenge for perceived victimization.

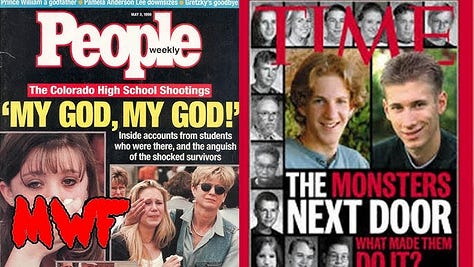

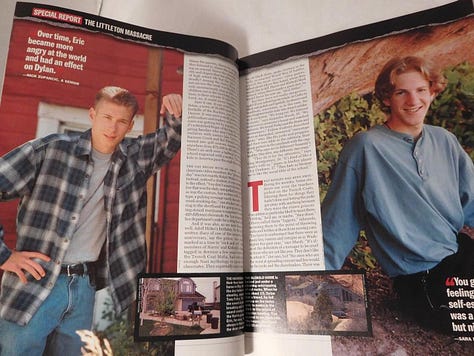

In an interview with Journalist’s Resource, Lankford, a criminologist, asks journalists not to “honor” mass shooters or suicide bombers by not publishing their names or pictures, which he somehow equates to honoring them.

Lankford says,

Our proposal is for media to keep reporting all the details about these crimes and these criminals that they would report anyways, but to make two small changes: Stop publishing the name of the perpetrator and stop publishing the photos or likenesses with the face of the perpetrator.

If we said, “the 2016 Orlando shooter,” rather than name him, we can still report all the details of that story without any problem. And in terms of the photo, I don’t think anyone really thinks that the photo itself is important as a newsworthy item. No one sees the photo of a mass shooter and thinks, “Aha, now that I have that information, I know how to stop mass shootings.” The photo is purely pandering to the public’s lurid curiosity and that’s specifically one of the things that the Society of Professional Journalists’ media ethics guidelines suggest should not be done.

He adds, later in the interview, that

the key is to deny these offenders the type of fame and type of advertising that is so destructive. And that is the front-page news, prime-time cable news, prominent online news and things like that.

The Society of Professional Journalists, which began its life as an all male Greek fraternity at DePauw University in Indiana before eventually admitting women and changing its name to the Society of Professional Journalists in the 1980s, says that it's “stated mission” is to “promote and defend the First Amendment guarantees of freedom of speech and freedom of the press; encourage high standards and ethical behavior in the practice of journalism; and promote and support diversity in journalism.”

Its advice to follow “high standards and ethical behavior” includes an admonition about not “pandering to lurid curiosity, even if others do,” and adds that “journalists have a moral imperative to jolt news audiences out of complacency from time to time, with “respectfully graphic” coverage of crime scenes that show the true effects of gun violence.”

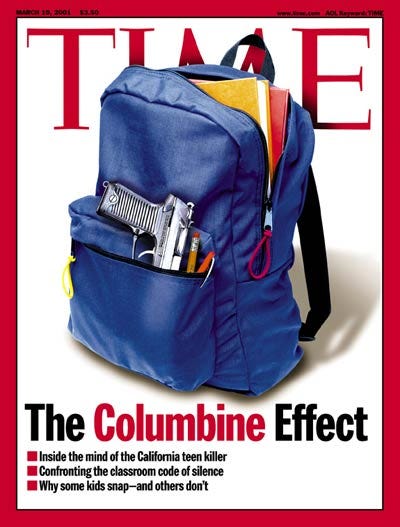

It is possible to publish both names and images of mass murderers without glorifying or romanticizing them in the way that, for instance, Ralph Larkin does in his book Comprehending Columbine, in which Larkin theorized that the Columbine massacre triggered a kind of slow revolution of outcast, bullied, and otherwise disenfranchised students.

Without directly naming Klebold or Harris, Larkin calls the Columbine massacre "An overtly political act in the name of oppressed students victimized by their peers…,” and goes on to say that, “The Columbine shootings redefined such acts not merely as revenge but as a means of protest of bullying, intimidation, social isolation, and public rituals of humiliation."

Putting this kind of romanticized spin on what amount to acts of both terrorism and mass murder is gross, and also seems likely to inspire copycats who can identify with these feelings and are attracted to the perceived glamor of the romantic mirage theorists have constructed out of what is likely their own pathos.

And yet the target of criticism is journalists and true crime reporting. These criticisms sometimes even come from people who teach journalism, some of whom have called true crime reporting harmful and unethical.

Lankford considers public advertising surrounding smoking, drunk driving, and reporting that redacts the names of victims of sex crimes as precedents for his “don’t name them” campaign, in which he argues that there is no public interest in knowing the identity and background of murderers.

These all seem like a false equivalency. Victims aren’t perpetrators, and neither are public service ads. No one has ever called hiding things the best disinfectant. The recent shooting in Madison demonstrates that the truth is far superior to idle speculation, which carries far greater risks.

Social media accounts first claimed that Rupnow was a radicalized transgender activist, and then a radical feminist who wanted to kill all men, but according to a manifesto leaked to social media by the shooter’s boyfriend, Rupnow was a white supremacist and racist in addition to being a rambling, barely coherent nihilist, brimming with both self hatred and a superiority complex.